The measurement of wellbeing

1. Comparing outcomes

How should we compare the impact of various outcomes, such as improving health or reducing poverty, in terms of how much good they do?

The most common method relies on subjective judgements; the value of different outcomes are weighed in the mind. Health metrics such as QALYs and DALYs, which rely on other people’s aggregated subjective judgements, are often used. However, health is not the only item of interest and subjective judgements are still needed to decide how the value of health outcomes should be compared to other outcomes.

The charity evaluator, GiveWell, determines the value of different interventions by asking their donors for their preferences between averting different numbers of deaths at different ages. They aggregate those preferences into a coherent set of moral weights across ages, and combine that with other inputs including the views of their staff and beneficiaries. You can read more about their approach here.

You might think that relying on subjective judgements of value is both unobjectionable and unavoidable on the grounds we are making moral evaluations, and there is simply no other way to do this. However, the claim these are moral judgements is only partly true and, indeed, may not be true at all. Some of what appear to be moral evaluations are judgements about facts and so, in principle, empirical questions.

1.1 Facts and values

Here’s an analogy. Suppose you and I are trying to determine which of two oddly-shaped jars contains the most water. What sort of assessment are we making here? Not a moral judgement, but a subjective judgement of fact. We could go on to say the best jar is the one that holds the most water, which would be a moral judgement.1 Assuming we mean ‘best’ in a moral, rather than merely aesthetic, sense.

Now, suppose you and I are trying to assess which of two outcomes increases wellbeing the most: curing health condition A or alleviating poverty by amount B. Suppose we agree on our concept of wellbeing. Are we making a moral evaluation when we state which outcome we think would increase wellbeing more? Clearly, as the jar analogy showed, we are not. We need not assume wellbeing is of any moral importance – perhaps we conclude only liberty has value – to compare the outcomes.

By contrast, deciding (a) which thing(s) are intrinsically valuable and thus constitute the good(s), and (b) how to aggregate the good(s) to determine overall value (in philosophical jargon, an axiology – the method of ranking states of affairs in terms of their ultimate value) is, certainly, a moral judgement.2 Technically, (a) and (b) suffice only to give us a fixed-population axiology. A third component (c), specifying who the bearers of value are (i.e. present, actual, necessary or possible people) is needed to give us a variable-population axiology. Perhaps confusing, what philosophers call a ‘population axiology’ usually just specifies (b) and (c).

Suppose, for example, we decide the value of an outcome is the sum total of wellbeing in it. That is a moral judgement. However, now we’ve taken that as given, determining how much good an outcome contains is, in principle, an empirical question. Those will be judgements of fact, not of value.

I hope it’s obvious that we will, where possible, want to measure the good(s) directly, and that objective measurement of the facts ‘trumps’ our subjective evaluations of the facts. If we could measure the water capacity of the jars, there would be no need to guess.

1.2 Productive disagreements

If we want to have productive disagreements with one another about which outcomes do more good, it’s important to make it clear whether disagreements arise from claims about value or from claims about facts.

Suppose you and I disagree about whether option A is better than option B. If we have the same views on value, the disagreement is a factual one.3 Both think the value of a state of affairs is the total wellbeing of those who exist in that state of affairs (hedonic totalism?) By comparison, GiveWell’s analysis combines the opinions of multiple people who have different views about value, it’s not possible to tell whether one disagrees with GiveWell because one differs about facts or about values.

The key question in GiveWell’s cost-effectiveness analysis is “how many years of doubled consumption are as morally valuable as saving the life of an under-5-year old child?” Here is a non-exhaustive list of factors two people could disagree about when answering that question, and whether that factor is a question of fact or value.

Table 1: List of factors

| Factor | Fact or value? |

| How much does doubling consumption for a year increase wellbeing? | Fact (for a given account of wellbeing) |

| What is wellbeing? | Value |

| How much wellbeing would the child have had if it lived? | Fact (for a given account of wellbeing) |

| How many years will the child live? | Fact |

| What is the badness of death? (i.e. is it better, all else equal, to save a 2-year-old or a 20-year-old?) | Value |

1.3 Our approach

At the Happier Lives Institute, our research focuses on how much different outcomes improve wellbeing. While this has generally been judged subjectively in the past, we believe it is a question of fact, not of value. Despite long-standing doubts, wellbeing can be measured through population surveys and therefore we should use data from wellbeing surveys, rather than relying on our own subjective judgements, to determine what increases wellbeing. Specifically, we recommend life satisfaction scores, which are found by asking “How satisfied are you with your life nowadays?” (on a scale from 0 “not at all” to 10 “completely”) as the most suitable (although not ideal) measure of wellbeing.

2. Subjective wellbeing

Social scientists (mostly economists and psychologists) talk about measures of ‘subjective wellbeing’ (SWB), which are “ratings of thoughts and feelings about life” (Dolan and Metcalfe (2012). SWB is typically thought to have three components (OECD 2013):

- Experience (sometimes called ‘affective’ or ‘hedonic’)

A person’s feelings or emotional states, typically measured with reference to a particular point in time. - Evaluation (sometimes called ‘cognitive’)

A reflective assessment of a person’s life or some specific aspect of it. Life satisfaction is a life evaluation question but not the only one - Eudaimonia

A sense of meaning and purpose in life, or psychological functioning.

For a list of example SWB questions, see OECD (2013, Annex A).

Measures of SWB are often referred to as measures of ‘happiness’. This is technically incorrect and also misleading. If we define happiness as a positive balance of enjoyment over suffering, then the experience component of SWB is identical with happiness. Evaluations measure how people feel about their lives, rather than how happy they feel during them. Eudaimonic measures may tap into psychological states – ones related to meaning – that, presumably, feel enjoyable to experience and thus comprise happiness, but do not capture all the psychological states relevant to happiness. Hence, SWB is not only a measure of happiness.

2.1 Experience measures

The ‘gold standard’ for measuring happiness is the experience sampling method (ESM), where participants are prompted to record their feelings and possibly their activities one or more times a day.4 Arguably, an even better method would be to measure brain waves, assuming we could correlate wellbeing with brain states. While this is an accurate record of how people feel, it is expensive to implement and intrusive for respondents. A more viable approach is the day reconstruction method (DRM) where respondents use a time-diary to record and rate their previous day. DRM produces comparable results to ESM, but is less burdensome to use (Kahneman et al. 2004).

2.2 Evaluative measures

Given we are interested in measuring happiness, we might think we should ignore the non-experience components altogether. Practically, however, this is unfeasible and we are forced to rely on life satisfaction measures as the main proxy measure for happiness (a ‘proxy’ measure is an indirect measure of the phenomenon of interest).

It is much easier to collect LS data as it requires just one quick question that takes subjects around 30 seconds to answer, whereas the DRM takes approximately 40 minutes to fill out. As a result of this ease of use, it is the SWB measure on which most data has been collected and most analysis done. It is now possible to say to what extent various outcomes cause an absolute increase in life satisfaction on a 0-10 scale, which is what we need to determine cost-effectiveness (see Layard et al. 2018). By contrast, to the best of our knowledge, there is insufficient research on experience measures to draw the same sort of conclusions.

2.3 Evaluative vs. experience measures

How much of a problem is it to use evaluative measures in lieu of experience ones? Experience and evaluative measures are conceptually different and answered in somewhat different ways. As Deaton and Stone (2013) explain:

Hedonic [i.e. experience] measures are uncorrelated with education, vary over the days of the week, improve with age,and respond to income only up to a threshold. Evaluative measures remain correlated with income even at high levels of income, are strongly correlated with education, are often U-shaped in age, and do not vary over the days of the week (Stone et al. 2010; Kahneman and Deaton 2010).

This doesn’t mean evaluative measures can’t be used as proxies for happiness. The evaluative and experience measures do correlate, suggesting evaluative judgements are, in part if not in whole, determined by how happy people are (OECD 2013, p32-34). While Deaton and Stone identify some cases where they come apart, it’s unclear if there are (many) cases where they reveal different priorities for philanthropists or policymakers who wish to maximise life satisfaction rather than happiness.

2.4 Which measures should we use?

The sensible approach seems to be to use happiness data where it’s available, but life satisfaction data where it isn’t and, when using LS data to determine cost-effectiveness, to keep in mind how the two might differ. Further work to investigate if, and when, using one measure over another would generate different priorities is urgent and valuable.

While eudaimonia measures are regarded as a component of SWB, we will not refer to them again. Not only are they not the most relevant component, little data has been collected on them and it’s not conceptually clear what they capture.

3. A brief history of measuring wellbeing

There are long-standing doubts (in economics) that wellbeing can be, or needs to be, measured. According to Layard (2003):

In the eighteenth century, Bentham and others proposed that the object of public policy should be to maximise the sum of happiness in society. So economics evolved as the study of utility or happiness, which was assumed to be in principle measurable and comparable across people. It was also assumed that the marginal utility of income was higher for poor people than for rich people, so that income ought to be redistributed unless the efficiency cost was too high.

All these assumptions were challenged by Lionel Robbins in his famous book on the Nature and Significance of Economic Science published in 1932. Robbins argued correctly that, if you wanted to predict a person’s behaviour, you need only assume he has a stable set of preferences. His level of wellbeing need not be measurable nor need it be compared with other people. Moreover, economics was, as Robbins put it, about “the relationship between given ends and scarce means”, and how the “ends” or preferences came to be formed was outside the scope of the discipline.

3.1 New momentum

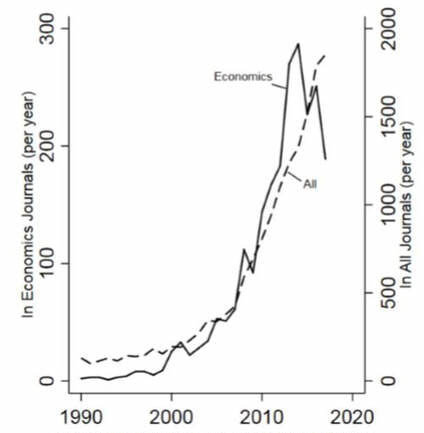

Interest in measuring happiness has returned in recent decades (see Figure 1).5 OECD (2013, p20) notes “during the 1990s there was an average of less than five articles on happiness or related subjects each year in the journals covered by the Econlit database. By 2008 this had risen to over fifty each year”.

Figure 1: Development of happiness-related publications

Note: Number of papers in the EconLit and Web of Science databases with reference in the title or abstract to: subjective wellbeing, subjective well-being, life satisfaction, happy, or happiness.

This seems to be caused by the Easterlin paradox, the (contested) finding that while richer people are more satisfied with their lives than poor people, an increase in average wealth does not raise average life satisfaction.

The idea governments should measure wellbeing and use it to guide policy has started to take root. In 2013, the OECD issued guidelines recommending its member nations collect SWB data:

There is now widespread acknowledgement that measuring subjective well-being is an essential part of measuring quality of life alongside other social and economic dimensions […] The Guidelines also outline why measures of subjective well-being are relevant for monitoring and policy making.

The UK’s Office of National Statistics has been collecting data on subjective wellbeing since 2012 and currently polls 158,000 people a year. (Readers unfamiliar with SWB measures may find their FAQs helpful.)

Now, some scholars who argue we shouldn’t use SWB measures, such as Fleurbaey, Schokkaert and Dencanq (2009), nevertheless accept such measures are meaningful:

With the mass of data accumulated on happiness and satisfaction and the development of their econometric exploitation, subjective utility seems more measurable than ever. There now seem to be good reasons to trust the existence of sufficient regularity in human psychology, so that interpersonal comparisons appear feasible in principle. These new developments have triggered a revival of welfarism as well. If utility can be measured after all, why not take it as the metric of social welfare? Several authors have taken this line (Kahneman et al. 2004b, Layard 2005). However, none of the recent developments in the field of measurement directly undermine the arguments that were raised against welfarism in the philosophical debates of the previous decades. The fact that something becomes easier to measure does not give any new normative reason to rely on it.

4. Validity and reliability

How confident can we be that subjective wellbeing (SWB) measures are accurate? Do they succeed in measuring what they set out to measure?

In the social sciences, the accuracy of a measure is usually assessed in terms of its validity and reliability.

Validity refers to whether the measure captures the underlying concept that it purports to measure. Suppose I try to measure your height by weighing you on a set of bathroom scales. The scales might be a valid measure of weight but it’s clear, I hope, they are not a valid measure of height.

Reliability is about whether the measure gives consistent results in identical circumstances (i.e. it has a high signal-to-noise ratio). If my scales produce a random number every time I step on them, they are not reliable.

Reliability is necessary but not sufficient for validity. If you used a normal, non-broken set of scales to measure your height it would give you the same score, and so be reliable (assuming your weight doesn’t fluctuate), but still wouldn’t be valid. The reliability and validity of SWB scales have been covered at great length in (OECD, 2013) and elsewhere. The following sections provide a summary of the key points.

4.1 Assessing reliability

Reliability can be assessed in two ways:

- Internal consistency – whether the items with a multi-item scale correlate or different scales of the same measure correlate.

- Test-retest reliability – where the same question is given to the same respondent more than once at different times. If the item in question genuinely does change between measures, we would expect the test-retest reliability to be low.

Regarding life evaluations, quoting (OECD 2013, p45):

Bjornshov (2010), for example, finds a correlation of 0.75 between the average Cantril Ladder measure of life evaluation from the Gallup World Poll and life satisfaction as measured in the World Values Survey for a sample of over 90 countries. […] Test-retest results for single item life evaluation measure tend to yield correlations of between 0.5 and 0.7 for time period of 1 day to 2 weeks (Krueger and Schkade, 2008). Michalos and Kahlke (2010) report that a single-item measure of life satisfaction had a correlation of 0.65 for a one year period and of 0.65 for a two-year period.

And regarding affect/experience measures:

There is less information available on the reliability of measure of affect and eudaimonic well-being than is the case for measures of life evaluation. However, the available information is largely consistent with the picture for life satisfaction. In terms of internal consistency reliability, Diener et al. (2009) report […] the positive, negative and affective balance subscale of their Scale of Positive and Negative Experience (SPANE) have alphas of 0.84, 0.88, and 0.88 respectively. […] In the case of test-retest reliability, […] Krueger and Schkade (2008) report test-retest scores of 0.5 and 0.7 for a range of different measures of affect over a 2-week period.

The authors of OECD (2013) conclude that life evaluation and affect measures exhibit sufficient correlation, by the standards of social science, to be deemed acceptably reliable.

4.2 Assessing validity

Validity, by contrast, is somewhat harder to test than reliability for SWB measures because the underlying phenomena are subjective, hence there is no objective way to demonstrate success. If you could measure something subjective objectively, it would not be subjective. Nevertheless, there are various ways to assess validity. All of these ultimately rely on whether the measures conform to our expectations about the item we are intending to measure.

The first is face validity – do respondents judge the questions as an appropriate way to measure the concept of interest? If not, it’s likely the measures aren’t valid. In the case of SWB measures, it’s somewhat obvious this is the case, e.g. that asking people whether they felt sad yesterday is a good way to assess whether they felt sad yesterday. Participants aren’t generally asked about face validity, but this can be tested by (a) response speed and (b) non-response rates: if people don’t take a long time, or don’t answer, that suggests they don’t understand the question. Median response rates for SWB questions are around 30 seconds for single-item measures, suggesting the questions are not conceptually difficult (ONS, 2011). Quoting from (OECD 2013, p47): “in a large analysis by Smith (2013) covering three datasets […] and over 400,000 observations, item-specific non-response rates for life evaluation and affect were found to be similar for those for [the straightforward] measures of educational attainment, marital and labour force status” which, again, supports the face validity of the questions.

The second is convergent validity – does the item correlate with other proxy measures for the same concept? Kahneman and Krueger (2006) list the following as correlates of both high life satisfaction and happiness: smiling frequency; smiling with the eyes (“unfakeable smile”); rating of one’s happiness made by friends; frequent verbal expressions of positive emotions; happiness of close relatives; self-reported health. In addition, OECD (2013) states:

Diener (2011), summarising the research in this area, notes that life satisfaction predicts suicidal ideation (r=0.44) and the low life satisfaction scores predicted suicide 20 years later in a later epidemiological survey from Finland (after controlling for other risk factors). Such items allow us to assess the measures from the perspective of falsifiability: if we expect that (say) those with low life satisfaction would commit suicide more often, but our measure of life satisfaction found those with high LS commit suicide more often, that would suggest the measure lacked validity. As it stands, the results support the validity of the experience and evaluation measures of SWB.

The third is construct validity – while convergent validity assesses how closely the measure correlates with other proxy measures of the same concept, construct validity concerns itself with whether the measure performs in the way we expect it to. From OECD (2013, p49):

Measures of SWB broadly show the expected relationship with other individual, social and economic determinants. Among individuals, higher incomes are associated with higher levels of life satisfaction and affect, and wealthier countries have higher average levels of both types of subjective well-being than poorer countries (Sacks, Stevenson and Wolfers, 2010). At the individual level, health status, social contact and education and being in a stable relationship with a partner are all associated with higher levels of life satisfaction (Dolan, Peasgood and White, 2008), while unemployment has a large negative impact on life satisfaction (Winkelmann and Winkelmann, 1998). Kahneman and Krueger (2006) report intimate relations, socialising, relaxing, eating and praying are associated with higher levels of positive affect; conversely, commuting, working and childcare and housework are associated with low level of net positive affect. Boarini et al. (2012) find that affect measures have the same broad set of drivers as measures of life satisfaction, although the relative importance of some factors changes.

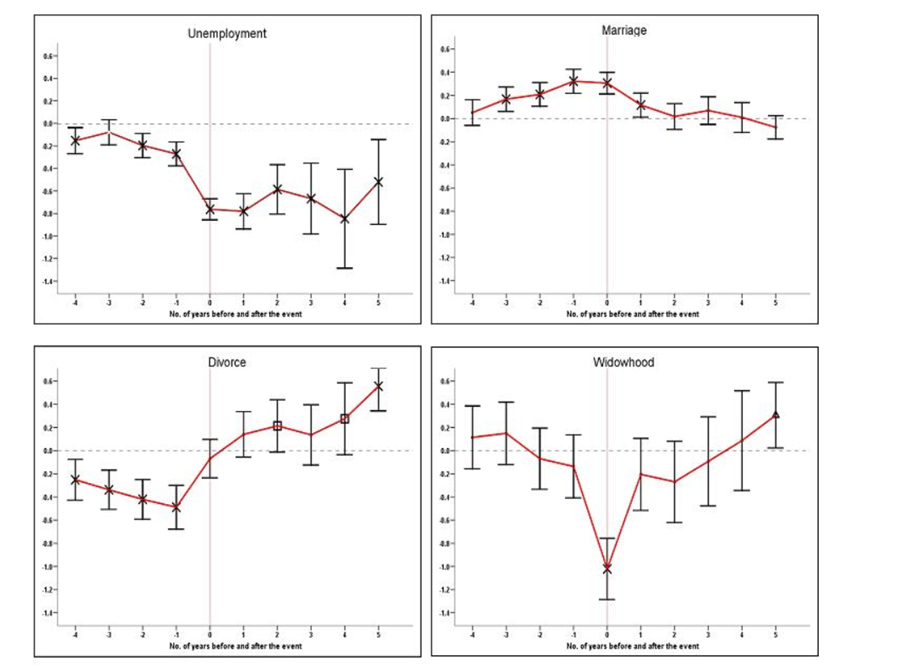

Major life events, such as unemployment, marriage, divorce and widowhood, are shown to result in long-term, substantial changes to SWB, just as one would expect them to. The time-series in Figure 2, from Clark, Diener, Geogellis and Lucas (2007), displays the LS-impact of such events for males (controlling for other variables) before, during and after they occur (y-axis records the change in LS on a 0-10 scale; the results are similar for females). Note the time series sometimes shows anticipation of the event. We can see, for example, a decrease in LS leading up to a divorce, whereas widowhood is barely anticipated and comes as a huge shock.

Figure 2: The dynamic effects of life and labour market events on life satisfaction (male)

Note: The y-axis represents the absolute change in life satisfaction on a 1-10 scale (Clark, Diener, Geogellis, and Lucas, 2007)

Figure 3 from Clark, Fleche, Layard, Powdthavee, Ward (2017, p100) shows a similar time series, this time for disability from three different data sets. Individuals seem to partially, rather than fully, adapt to disability.6 In a meta-analysis, Luhmann et al. (2012) compare the rates of adaptation on evaluative and experience measures of SWB, finding some differences. This is what we might suppose would happen: becoming disabled is very bad, but being disabled is somewhat less bad as one’s lifestyle and mindset adjusts. It’s worth noting here one major potential objection to the use of SWB measures is that people do not really adapt to changes in circumstances, they simply change how they use their scales. However, if scale re-norming did take place, we would expect to see adaptation to all conditions. Yet, we do not see this: the LS scores in Figure 2 above show people adapt to some things and not others. Further, Oswald and Powdthawee (2008) find there is less adaptation to severe disability than to mild or moderate disability, suggesting scale norming is not occurring and that the SWB scores are reflecting reality.

Figure 3: Adaptation to disability in different country data-sets

Note: From Clark et al. 2017, p100

As mentioned before, if the SWB measures had produced counter-intuitive results (the ‘wrong answers’) that could lead us to conclude they were not valid. Yet, the above seems to match our ‘folk psychological’ expectations.

4.3 The Easterlin Paradox

One finding that might, at least at first, seem counterintuitive is the relationship between SWB and income. While there is little disagreement that richer people within a given country report higher SWB (both on experience and evaluation measures), and richer countries report higher SWB, there is less consensus over whether SWB increases over time as countries become wealthier. This is the so-called ‘Easterlin Paradox’, displayed in Figure 4 below Clark et al. (2018, p203). A critical response to SWB measures could be made as follows: “the Easterlin Paradox shows increasing overall economic prosperity doesn’t increase SWB. But it’s obvious increasing overall economic should raise SWB. Therefore, the SWB measures must be wrong”.

Such a response would be too quick. First, the debate still rages over whether the Easterlin Paradox holds – Stevenson and Wolfers (2008) argue it does not, Easterlin et al. (2016) reply. Second, as Clark (2016) notes, a large body of research finds individual SWB depends not just on the individual’s own income, but also their income relative to that of the reference group they compared their own income to. Thus, if I am wealthier than you, I should expect to have higher SWB. However, if my income rises but the income of those I compare my income to also rises, these effects cancel out, leaving my SWB unchanged. Hence the Easterlin paradox can be explained in large part by the phenomenon of social comparison: we judge our lives against those of others.

Figure 4: Change in subjective wellbeing and GDP/head over time

In a particularly insightful study, Solnick and Hemenway (2005), individuals were asked to choose between different states of the world, as follows.

A: Your current yearly income is $50,000; others earn $25,000

B: Your current yearly income is $100,000; others earn $200,000

Absolute income is higher in B than in A, while relative income is higher in A than in B. Individuals express a marked preference for A, highlighting the importance of relative income. Hence, with further analysis, the Easterlin paradox is no longer as counter-intuitive as it first seemed.

Overall, the evaluation and experience SWB measures seem both reliable and valid.

5. Comparing individuals

For a given subjective wellbeing (SWB) scale, say life satisfaction, is going from 7 to 8 for one person equivalent to another person going from 2 to 3? This is the question of whether the scales exhibit interpersonal cardinality. Let’s unpack this concern in stages.

5.1 Are SWB scales cardinal or ordinal?

The first question to ask is: does the underlying phenomena of interest – the thing the SWB scales are trying to measure – have a cardinal structure, or is it merely ordinal? That is, it represents something that can be quantified – like length, height, weight, etc. – or does it merely represent an ordering – like ‘A is taller than B’? (1st, 2nd, 3rd … are the ordinal numbers, 1, 2, 3, … are the cardinal numbers).

It is intuitively obvious that happiness is cardinal, as revealed by our linguistic use. It is entirely sensible to say “X hurt twice as much as Y” or “I feel 10 times better than I did yesterday”.7 A doubt here is whether, given the diversity of experiences, there is any one property that all happy (and unhappy) experiences have, such that we can quantify them on a single scale. Following Crisp (2006) I think there is: the property of pleasantness, or ‘hedonic tone’. Even though headaches and heartbreaks feel different, I find nothing confusing in saying one can feel as bad as another. For dissent, see, e.g. Nussbaum (2012) If happiness were ordinal, the most we could say would be “X hurts worse than Y” and “I feel better today than I did yesterday”.

If life satisfaction scales capture a psychological state of satisfaction, then this would be cardinal; as above, intuitively, one can feel twice as satisfied about X vs Y.8 An alternative motivation for measuring life satisfaction is that it captures a cognitive judgement of the extent to which someone’s preferences are satisfied – i.e. the world is going the way they want it to – rather than a feeling. If unclear if preferences can be cardinal. As Hausmann (1995) argues at length, while we can order preferences (preferences are about how entire worlds go), there is in principle no conceptual unit of distance between our ranked preferences to generate cardinality. This is too much of a diversion to discuss further here. Given we are ultimately interested in happiness here, and evaluations are relevant only as proxies for, it seems convenient to side-step the problem say evaluations capture a felt strength of satisfaction.

5.2 Are SWB scales linear or logarithmic?

Given the underlying phenomena of interest has a cardinal structure, the next question is whether individuals’ reporting on the scale is equal-interval (another term for this is linear), i.e. going from 5/10 to 6/10 is an equivalent improvement as going from 7/10 to 8/10. One worry is that individuals interpret SWB scales as logarithmic, like the Richter scale, where the magnitude of going from 6/10 to 7/10 is 10 times that of going from 5/10 to 6/10, rather than as linear/equal-interval.9 The worry individuals may self-report in this way has been raised with me separately by Toby Ord and James Snowden.

While possible, non-linear reporting seems unlikely.10 If it turned out reported SWB was a function of log(actual SWB) that wouldn’t make it impossible to make interpersonal cardinal comparisons: we simply need to convert individuals’ scores onto a linear scale. Experimental evidence from Van Praag (1993) suggests that when presented with a number of (non-SWB-related) points, respondents automatically treat the difference between points as roughly equal-interval. Further, it is intuitively much harder for ordinary people (i.e. non-mathematicians) to report how happy/satisfied they feel on a logarithmic scale than on a linear one. If I ask myself “how happy am I right now on a 0-10 logarithmic scale?” to try to answer this question I first have to think “how happy am I on a linear, 0-10 scale?” I then try to remember how logarithms work and convert from there. This is so much harder to do that I assume scale use must be equal-interval.

5.3 Interpersonal cardinality

Given the scales have intrapersonal cardinality, the final question is whether they have interpersonal cardinality: is one person’s reported one-point increase on a 0 to 10 scale equivalent to a one-point increase for someone else?

There are two different concerns here. First, individuals could correctly report where they are between the minimum and maximum points of the scales but have different capacities for SWB. There could be ‘utility monsters’ who experience 1000 times more happiness than others. Second, individuals could have the same maximum and minimum capacities but use the scales differently. Suppose almost everyone reports a given sensation as 6/10, but a few people report the same feeling as an 8/10; keeping the same terminology, this latter group are ‘language monsters’.

We can make the same reply to both concerns. So long as these differences are randomly distributed in the surveyed population, they will wash out as ‘noise’ across large numbers of people: there will be as many people with a greater capacity for SWB as those with less, and as many who use the scale too conservatively as use it too generously.

Specifically, in response to utility monsters, it seems unlikely, given our shared biology, that the utility capacities of humans will, in practice, vary by very much.11 We might reasonably worry this assumption does not hold if we wished to compare current humans to either (a) non-human animals or (b) some hypothetical future humans that are genetically modified to be happier. These are not issues that need trouble us here.

Regarding the language worry, I observe we do tend to, in general, regulate one another’s language use. For instance, if I say “I’m having a terrible day: I stubbed my toe” you are likely to say “Hold on. That’s not a terrible day. That’s a mildly bad day”. A hypothesis, which could conceivably be tested, is that this language regulation pushes us towards using SWB scales in a similar way. If language did not have a shared meaning, it would be of no use at all.

We might object to this last point that, even if groups regulate their members’ language use, different groups could still use scales differently. As an empirical test on this, a study by Helliwell et al. (2016) of immigrants moving from over 100 different countries to Canada found that, regardless of country of origin, the average levels and distributions of life satisfaction among immigrants mimic those of Canadians, suggesting LS reports are primarily driven by life circumstances. If there really was a substantial cultural difference in LS scale use, this result would not occur.

Therefore, it seems reasonable to interpret SWB data as interpersonally cardinal. However, as this point seems important, more work here would be welcome.

6. Wellbeing-adjusted life years

Suppose we accept we can use life satisfaction (LS) scores to measure happiness. What next? One, straightforward option would be to measure LS (and other subjective wellbeing (SWB) metrics) impacts directly in randomised controlled trials. If we know the costs of a programme, we could then establish how much it costs to produce one ‘life satisfaction point-year’ or ‘LSP’ – equivalent to increasing life satisfaction for one person by one point on a 10 point scale for a year. This method is structurally similar to assessing cost per quality-adjusted life year (QALY) except that QALYs are measured on a 0-1 scale whereas LS is on a 0-10 scale.

Table 2: How adult life satisfaction (0-10) is affected by current circumstances

| Effect on life satisfaction (0-10) | Total effect on the life satisfaction of others (0-10) | |

| Income doubles | +0.12 | -0.13 |

| One extra year of education (direct effect) | +0.03 | -0.09 |

| Unemployed (vs. employed) | -0.70 | -2.00 |

| Quality of work (1 SD extra) | +0.40 | – |

| Partnered (vs. single) | +0.59 | +0.68 |

| Separated (vs. partnered) | -0.74 | – |

| Widowed (vs. partnered) | -0.48 | – |

| Being a parent | +0.03 | – |

| One physical illness | -0.22 | – |

| Depression or anxiety | -0.72 | – |

| Commit one crime | -0.30 point-years | -1.00 point-year |

Note: From Clark et al. 2018, p199

6.1 WELLBYs > QALYs

QALYs capture health, and as I noted at the start, not only is health not all that matters, we will still need a common currency that allows health and non-health outcomes to be traded-off against one another, and a non-arbitrary method to determine the value of outcomes in this currency.

LSPs could partially or fully fulfil the role of being the WELLBY metric. For those who think happiness is the only intrinsic good, LSPs should be sufficient – unless and until a better measure of happiness can be found. Those that value goods other than happiness will, presumably, value happiness to some extent, and inasmuch as they do, LSPs will be one aspect of WELLBYs they need to consider alongside other goods.12 Suppose someone thought there are two intrinsic goods, happiness and autonomy. They would need a measure of autonomy – autonomy-adjusted life years (AALYs)? – and they would need to set up a conversion rate between LSPs and AALYs to determine which outcome did the most good on the composite measure.

6.2 Data collection and RCTs

Data from randomised controlled trials using LS will not always be available. Where it is not, an alternate way to determine how different outcomes affect LS is to rely on data from large population surveys. Using a multivariate regression analysis that controls for different circumstances, researchers can then estimate the strength of the correlations between LS and various other factors. Table 1 from Clark et al. (2018, p199) contains the results of such an analysis both for the impact a given change has on an individual’s LS and that which it has on others.

This information can be used to make inferences about the expected LS effect of a given outcome without requiring a randomised controlled trial, at least if it’s straightforward to measure the outcome, as it is in cases of unemployment for example. In other cases, the relationship between life satisfaction and other measures, such as particular health metrics, will need to be established so other metrics can be converted into LS scores. Some of this work has been done: see Layard (2016) for such a table converting LS scores into both other SWB measures and various health metrics.

Three remarks on the results in the table that will be relevant again shortly:

- Doubling income is associated with a constant increase in life satisfaction.

- The gain one individual receives from a doubled income causes a nearly equally large equivalent loss in LS to others.

- Mental health, employment, and partnership have a much bigger per-person impact than a doubling of income does (for the individual whose income increases).

While it is already possible to estimate the LS effect of many outcomes, this task will become much easier if researchers can be encouraged to collect wellbeing data alongside other variables. This only requires quickly surveying individuals at the start and end of an impact assessment. This generates extra work but also allows direct measurement of the outcome that is (presumably) of most interest.

7. The problem with health metrics

Researchers have tended to use health metrics (QALYs and DALYs) as the proxy for wellbeing-adjusted life years (WELLBYs). However, these standard health metrics are misleading proxies for wellbeing. For ease, we quote at length from Clarke et al. (2018, p85):

In the QALY system, the impact of a given illness in reducing the quality of life is measured using the replies of patients to a questionnaire known as the EQ5D. Patients with each illness give a score of 1, 2, or 3 to each of five questions (on Mobility, Self-care, Usual Activities, Physical Pain, and Mental Pain). To get an overall aggregate score for each illness a weight has to be attached to each of the scores. For this purpose members of the public are shown 45 cards on each of which an illness is described in terms of the five EQ 5D dimensions. For each illness members of the public are then asked,“Suppose you had this illness for ten years. How many years of healthy life would you consider as of equivalent value to you?” The replies to this question provide 45N valuations, where there are N respondents. The evaluations can then be regressed on the different EQ5D dimensions. These “Time Trade-Off” valuations measure the proportional Quality of Life Lost (measured by equivalent changes in life expectancy) that results from each EQ5D dimension.

As can be seen, these QALY values reflect how people who have mostly never experienced these illnesses imagine they would feel if they did so. A better alternative is to measure directly how people actually feel when they actually do experience the illness.

The result would be very different. Figure 5 contrasts the outcomes from these two different approaches. The existing QALY weights are shown by the shaded bars of Figure 5. This scale has been normalized so that the bars can be compared with those from a regression of life satisfaction on the same variables. This latter regression is shown in the black bars in the figure—the magnitudes here are not β-statistics but the absolute impact of each variable on life-satisfaction (0–1). As can be seen from the lower part of the figure, the public hugely underestimated by how much mental pain (compared with physical pain) would reduce their satisfaction with life.

Figure 5: How life satisfaction and daily affect (0-1) are affected by the EQ5D, compared with weights used in QALYs

Note: Data from Dolan and Metcalfe, 2012

7.1 Imagination vs. experience

QALYs are not a very good guide to what makes people happy or satisfied because they are based on people’s preferences over how bad they imagine various health states are, rather than how bad they are when they experience them and we are not very good at imagining what makes us or others happy (see below).

To highlight a particularly outstanding discrepancy, Dolan and Metcalfe (2012, from whom the above Figure 5 is derived) report subjects agreed to hypothetically give up as many years of their remaining life, about 15%, to be cured of ‘some difficulty walking’ as they would to be cured of ‘moderate anxiety or depression.’ However, from SWB measures ‘moderate anxiety or depression’ is associated with 10 times a greater loss to life satisfaction, and 18 times a greater loss to daily affect, than ‘some difficulty walking’ is (note the time trade-off lines for ‘mobility 2’ and ‘anxiety 2’ in Figure 5 are the same length but the two SWB lines are very different).

This seems compelling evidence, if we need any, that if we rely on people’s preferences about imagined futures we will get the wrong answers about what makes individuals happy. Psychologists use the term ‘failures of affecting forecasting’ to refer to predictive mistakes we make when predicting what will make us and others happier in future. One reason for this is that, when imagining the future, we fail to anticipate that our ‘psychological immune system’ will ‘kick in’ and cause us to adapt to some circumstances but not others: what Gilbert et al. (1998) call ‘immune neglect’. Conditions such as mobility impairment are things we stop paying attention to, whereas mental illnesses are comparative ‘full-time’ and continue to affect our subjective experiences.

We are unaware of any studies comparing DALYs and SWB measures directly, but given how DALYs are constructed – typically by asking experts for ratings – we would expect the same problems to occur. See Sassi (2006) for a comparison of the methodologies for QALYs and DALYs.

7.2 Physical health vs. mental health interventions

An implication of this analysis is that we should substantially reduce how cost-effective physical health interventions are compared to mental health interventions, assuming we’d previously judged them by QALYs and DALYs (Giving What We Can 2015, 2016). By itself, this doesn’t mean mental health interventions are more cost-effective than physical health interventions. We need to say more about the costs and effects than this but it is a relatively big update in our analysis.

Perhaps the reason that mental health conditions have been largely overlooked is because of an overreliance on QALYs/DALYs as an approximation of wellbeing. Given how much QALYs underrate the badness of mental health, it’s not much of a surprise that individuals using those metrics would come to the conclusion that mental health is comparatively unimportant.